With the spectacular opening episode of this historical series, I wanted to point out that World War I ended neither with the armistice nor with the peace treaty. Shooting, fighting, conquering, occupying and liberating continued everywhere. The aftermath of the Great War will continue to haunt us for many episodes to come. Exactly one hundred years ago, in March 1921, for example, French and Belgian troops occupied parts of Germany, the Polish-Russian War was settled by the Treaty of Riga, and Emperor Charles I of Austria-Hungary attempted to coup his way back to power.

These are all interesting topics, but we are going further east today, where the aftermath not only of World War I, but also of the Russian October Revolution is raging. And how it is raging!

You know that already, from Doctor Zhivago, but contrary to popular myth, the carnage was not caused by the quarrel between Tonya and Lara. Russia, which hadn’t necessarily won World War I, but certainly hadn’t lost it either, and had been gifted with not one, but two revolutions, somehow didn’t manage to rest on its laurels. Instead, the October Revolution of 1917 was immediately followed by the Russian Civil War, which dragged on for another agonizing five years. Longer than the World War had lasted. And much more complicated.

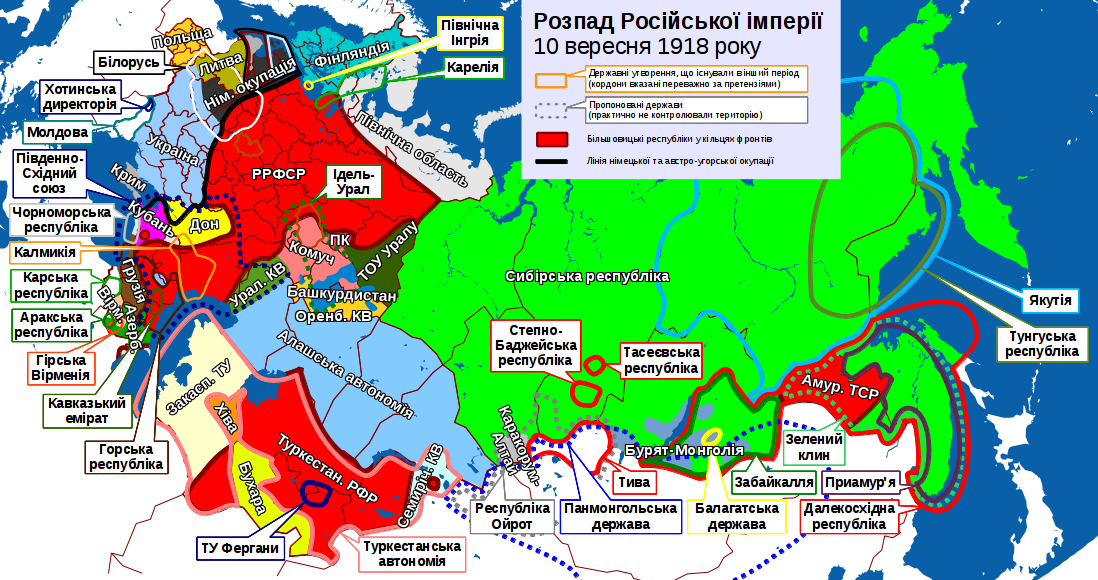

Simplifying drastically and not taking into account the heterogeneity of the warring parties, the military interference of Germany, France, Great Britain, the USA, Japan, the Ottoman Empire and the Czechoslovak Legion who took the wrong way and ended up in Siberia, nor the national independence movements in Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Abkhazia, Bessarabia and the People’s Republic of Tannu-Tuva, as well as the changing alliances, it was like this: There were the Reds and the Whites. The Reds were the Bolsheviks. The Whites were all those who were against the Reds, that is monarchists, democrats, nationalists and moderate socialists.

Got it?

Some advice for students of history: Never attend the lecture on the Russian Civil War! It’s like a four-dimensional labyrinth with mirror-inverted wormholes. You won’t find your way out of it ever again.

In order not to get bogged down in details, which is a constant danger on this blog, we leave the big picture and focus on just one person, following him for a few years through the Russian Civil War and a few hundred kilometers across the steppe. Or more like a few thousand kilometers, because Russia is huge.

That one person is, no, not Doctor Zhivago. It is a Baltic German baron, i.e. a member of that German-speaking upper class in Estonia and Latvia who, as descendants of the Crusaders, subjugated the Estonians and Latvians. Roman Nikolai Maximilian Feodorovich von Ungern-Sternberg was his name. (The history of the Baltic Germans would provide material for a hundred digressions, but I’ll write about them when I am in the Baltics again.) Because the Baltic Germans liked to maltreat people, the Russian tsar gladly recruited them for the administration or the military.

Roman, not having learned anything useful, was drawn to the army, too. He fought in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05, incidentally the first war that a European country lost against a non-European country. After that, he bummed around a bit, served with a Cossack regiment in Transbaikalia, got drunk too often, quit the service, rode his horse to Mongolia, where, for lack of anything else to do, he learned Mongolian and read up on Tibetan, Hindu and Buddhist teachings. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he returned to Estonia in time to invade East Prussia with the Russian army. (Ethnicity was not yet so important at the time of the multi-ethnic empires, and Germans fought Germans on other fronts as well. Each for his emperor or tsar, who were certainly grateful for it.)

And when the World War was over, there was this stupid revolution, which didn’t fit into the baron’s concept at all. For one thing, as a nobleman he was loyal to the tsar. For another, the Estonians were now independent and revolted against the German overlords.

Roman von Ungern-Sternberg sided with the Whites, no question. Granted, loyalty to the tsar had become a questionable concept after the tsar and his family had been murdered. But Bolshevism, where barons were relegated to earn the same as bus drivers, was nothing for the nobleman. He was also angry that the revolutionary people had set fire to his manor house and that he had to move into one of those prefabricated apartment blocks.

What’s a cavalry officer to do when everything is a pain in the horse’s butt? Naturally, he takes a horse and rides east. He robbed trains under the pretext of cutting off supplies for the Bolsheviks. He held up traveling merchants to extract “customs” payments from them. And soon, he was back in Transbaikalia, setting up an Asiatic Cavalry Division, made out of Mongols, Buryats, Kyrgyz, Manchurians, Tibetans, Kazakhs, Evenks, Uyghurs, Bargas.

With all the evils that henceforth emanated from this man, I don’t even know where to begin. If the Russian Civil War had already been extremely brutal, Ungern-Sternberg stepped it up a notch and became the most fearsome commander of the Whites. With bloodthirsty brutality, he murdered opponents, alleged opponents, prisoners, his own soldiers, civilians, and above all Jews. To Jews he gave no pardon, they were hunted down until the last child was slain.

At some point, it had nothing to do with the Russian Civil War any longer, which had become a hopeless cause for the Whites anyway. Unpleasant-Sternberg simply lived out his hateful anti-Semitism. He behaved like a warlord with a private army.

Because this is getting too bloodthirsty for us, we change the setting a bit and move south to Mongolia. It lies roughly between Russia and China and had been a Chinese province for 200 years at the time of our story. But China was having a bit of domestic trouble (a virus, production shortfalls in the Apple factory or trouble with students in Hong Kong, I don’t know), and the Mongol princes thought: “If such trifle countries like Lithuania or Czechoslovakia can become independent, so can we.” (Mongolia, even if you’ve overlooked it until now, is pretty large.)

You must know that the Mongols are mainly Buddhists and therefore have a chief lama called Bogdo Gegen. That is the title, not the name. Just like the Dalai Lama, who has the same job with the Tibetans. Exactly, this is the guy who is always smiling for no reason, who makes harmless statements that people put on their Instagraph too feel “enlightened”, and who has accomplished zero point zero for his people.

The Mongols, as I said, had known the Chinese for 200 years and knew: “Smiling won’t get us anywhere.” Instead, they elected the eighth Bogdo Gegen as Bogdo Khan, i.e. the ruler of Mongolia, which thus declared itself independent. The Mongols contacted the Russian tsar (before his assassination, obviously) and received a huge loan, which they invested in a winter palace that still exists in Ulan Bator today.

There, they prayed for independence.

When that didn’t help and, to make matters worse, their Russian sponsor was shot, the Mongol princes sent desperate pleading and begging letters around the world. (Just like princes from Nigeria do today.) Two hundred letters, three hundred letters, four hundred letters. All with pompous seals, written with camel blood and delivered by Mongolian eagles. Very impressive.

But nobody could read the letters. Because nobody spoke Mongolian.

Wait! You remember the Baron’s youth, when he studied Buddhism and Mongolian? He was constantly ridiculed for indulging in such Far Eastern ballyhoo instead of studying something solid like civil engineering or multimedia marketing, but now it was a sign of fate. His fate and that of the Mongols: Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg received one of those letters, summoned his multinational cavalry, bid adieu to the (already hopeless) fight against the Bolsheviks, and rode off toward Mongolia in August 1920. Of course not without looting and killing everything on the way.

Tragically, quite some time had passed since the letter was sent, and not as uneventfully as arrogant Westerners might imagine that time passes in Mongolia. In 1919, Chinese troops had regained control of Mongolia and deposed the Bogdo Khan in 1920. Nevertheless, during the long ride Ungern-Sternberg made the plan to unite all Central Asian peoples (Tibetans, Buryats, Uyghurs, Mongols, Kyrgyz, etc.) into a “Great Mongol Empire”, which should last forever and for all times as the monarchist bulwark against Europe and the civilizing bulwark against China. Nominally, Baron von Ungern-Sternberg was still fighting for the dead tsar, but in reality, he already saw himself as the new Genghis Khan.

In October 1920, the Asiatic Cavalry Division arrived in Urga (now Ulan Bator and still the capital of Mongolia) and was defeated twice by the numerically superior Chinese. Ungern-Sternberg deliberated for a few months, habitually passing the time by raiding villages and monasteries. Finally, in February 1921, he remembered a stratagem of Genghis Khan’s: He had fires lit on the hills around Urga to simulate a large army. The Chinese therefore did not throw the full defensive force at his cavalry, and the cavalrymen rode into the city, where they liberated the Bogdo Khan and put the Chinese troops to flight. (To avoid another such fiasco, China has since built the Great Wall and developed drones.)

Bogdo Khan and Roman von Ungern-Sternberg subsequently argued about who was the more important man in town. The Mongol invasion had gone to the baron’s head, and he saw himself as the reincarnation of Genghis Khan. The Bogdo Khan didn’t much warm to the idea of the Great Mongol Empire; Mongolia alone was big enough for him. Finally, the two agreed that Ungern-Sternberg would install the Bogdo Khan as ruler of the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Mongolia in March 1921, exactly 100 years ago. In return, the new king recognized the baron as the founder of the state, as a heroic general, and as the incarnation of the Tibetan patron deity Jamsaran, a particularly wrathful deity.

As is well known, the wrath fitted like a glove. The baron made it clear that he was the real boss and that the king only served as figurehead. He had lists drawn up of all the Jews living in Mongolia. Many of them had fled the Russian Civil War to the supposed safety of the Far East. But now Baron von Ungern-Sternberg went from house to house with anti-Semitic obsession to exterminate Jewry in Mongolia. Even the German occupiers 20 years later, known to be extremely fanatical, did not come this far east.

And for only one reason: Because Roman von Ungern-Sternberg was already dead. Otherwise, of course, he would have made a pact with the Wehrmacht to fight against Jews and Bolsheviks, his dearest enemies. In the end, we were saved from this by a rebellion of his own people, when the baron ranted about having to advance on Tibet next. That was too far and difficult (there were no trains to Lhasa at the time), and the guys arrested their leader and handed him to the Bolsheviks.

The trial was rather short, probably for a shortage of lawyers. Annoyed by the baron’s anti-Semitic tirades (“Bolshevism was invented by the Hebrews in Babylon 3,000 years ago”), the judge suggested if he wouldn’t perhaps simply want to be shot. Compared to other methods of execution, this was quite a concession. (Do keep that in mind if you’re ever in a similar situation.)

“I would prefer not to,” Roman von Ungern-Sternberg replied, but the objection died in the hail of bullets from the Kalashnikovs along with the German Genghis Khan.

Mongolia, by the way, remained independent. Today, there are still voices that revere Baron von Ungern-Sternberg as the founder of the country. But much more important seems to be the question where the baron buried his legendary gold treasure. That is why people are digging and burrowing everywhere in Mongolia.

You don’t have to dig that deep to find people in Mongolia whose fascination with history, with the German baron and with everything that Germany has exported to the wider world since then, is rather unclouded by historical judgment.

So much for the swastika apologists who always claim: “Well, in Buddhism it has a totally different meaning.”

Links:

- All articles of the series “One Hundred Years Ago …”.

- More history.

- More reports from Russia.

- Speaking of Far Eastern religious leaders: The next Dalai Lama once gave me a ride when I was hitchhiking. A very nice young man!

- Neo-Nazis are not only found in Mongolia, but also in Mexico, in Bolivia, in Colombia, and probably, NASA will soon discover some on Mars.

- If this article has provided you with an interesting topic for a presentation at school or has prevented you from an ill-advised trip to Mongolia, I would be happy about any support for this blog. In return, there will be many more curious stories from a hundred years ago, the effects of which we still encounter today.