When thinking about migration, we distinguish between push- and pull-factors when we try to get to the bottom of migrants’ and refugees’ reasons to move/flee. The former refer to incentives to leave a place and move away. Common causes are poverty, war, political or religious oppression. The latter try to explain why migrants choose a particular place as their destination. These may be economic opportunities or a preferred political system, but also linguistic or cultural proximity, more sunshine, or family members already living abroad.

Based on my own experience, I would like to add an often overlooked reason: Boredom. Or, to put it more positively: Curiosity. A sense of adventure. Wanderlust.

For me, the wish to see more of the world has always been the natural state of mind. Even as a child, I gazed longingly at the world map above my bed, devoured travel books (back then there was no interweb, let alone fantastic world travel blogs like this one), collected stamps from all over the world, looked up the places in the atlas, and brightened up every time I heard foreign languages on the radio or in the street.

The bad habit of spending one’s entire life in one place seems absurd to me, even unnatural, considering how diverse the world is. Perhaps this was still understandable in times when life expectancy was a meager 30 years, so that after high school, military service and university, only two years remained until death. (If you were very unlucky, those 30 years coincided with the Thirty Years’ War, the Eighty Years’ War or the Hundred Years’ War.) But now we are all going to become 80, 90 or 100 years old. If you don’t want to be bored to death, you have to move to another country every seven years at the latest!

Unfortunately, fate had condemned me not only to grow up in a boring little village in Bavaria, but had also punished me with a rather provincial family, for whom it would have been unthinkable to move further than 10 km from their birthplace.

I always wanted to leave that place. That’s probably why I became a globetrotter and a global citizen. In this respect, I can well understand that – to finally get to the actual story – my great-granduncle Josef Vogl emigrated from this farm in the Bavarian Forest to the USA exactly one hundred years ago, in June 1922.

Now, this does not exactly qualify as an event of world history, as most of the events covered in previous episodes of this small, but fine history series. But I would like to bother you with it nevertheless. For one, because the countless cases of this and similar emigrations together did make world history, in this specific case the emigration of millions of Germans all over the world. On the other hand, I would like you to join me on the trail of research, because I would not be surprised if your family history also contains hitherto unknown migration stories. (In the USA alone, 45 million people give their main ancestry as “German”, and in Canada, Australia, South Africa and Latin America, too, I have met a great many people with amazingly German/Austrian/Swiss sounding names.)

For me, curiosity was kicked off with two photos, taken around 1960, showing my father (the Elvis impersonator), my uncle (the Hitler impersonator), the rest of the extended family, and an unknown man who is obviously the center of attention.

“That was Frank from America,” my father says. Actually, his name was Franz. Franz Vogl, the younger brother of Josef Vogl. Both emigrated to the USA. Josef came to visit once after World War II, Franz/Frank returned twice. Each time at Pentecost, because there is always a hell of a party in Kötzting. Something like the Oktoberfest, but with horses.

“And they got mighty drunk,” my father remembers, “because Frank had dollars.”

Maybe it was because of that drunkenness, but that was all I could get out of my father and uncle. They did not know where in the USA their great uncles had lived. They did not know when and why they had emigrated. They did not know – beyond Franz Vogl’s wife shown in the photo – about any families, descendants and thus possible cousins and other relatives. They did not know whether they were Republicans or Democrats. They didn’t know what they had done in World War II. Nothing at all.

At some time in the 1960s, contact had broken off.

In our family, it is considered suspicious to leave one’s home and venture out into the world. Traveling is considered frivolous, a heretical attempt to leave one’s God-given place on Earth. As I said, I can understand why Josef and Franz wanted to leave. And so I am the only one who is interested in this story. But even I forgot about it for a while.

Until I was in New York again and took the ferry to the Statue of Liberty. That’s the lady with a torch reciting a poem that includes the call: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

That slogan is quite appropriate, because the Statue of Liberty was indeed the first thing to be spotted by most immigrants who came to New York by ship. Before they were allowed into the country, however, they landed on a neighboring island, Ellis Island, where, until 1954, the central immigration processing point of the USA was located.

Now the former holding room for immigrants is a museum. Here, you can learn how immigration policy changed over time, what requirements immigrants had to fulfill, how the medical examination and quarantine worked. I walked through the arrival hall, the doctors’ rooms and the dormitories, where my relatives felt solid ground under their feet again for the first time after crossing the Atlantic.

By the way: Make sure that you don’t accidentally take the ferry to Rikers Island instead of Liberty Island or Ellis Island. From there, you wouldn’t be able to leave that easily.

On Ellis Island, they had those new-fashioned computer terminals, where you could search for relatives – or for anyone, really. Practically like an archive, only without the romance of leafing through thick books for hours. I knew precious little except that there were two brothers, named Franz and Josef Vogl. Let’s see what I could find with that.

First, I learned that Vogl is a rather common name: 827 hits. (My great-granduncles had a different surname from mine because they come from a grandmotherly line and because the women in my family have not yet been emancipated enough to keep their surnames after marriage.) With my own last name, Moser, there are 6377 hits. Among them even 9 Andreas Moser, who emigrated to the USA between 1866 and 1936. Oh, if only I had met one of them by chance in the port tavern before departure. I might have snatched the ticket from him and used it myself.

If you know the year of birth, the year of emigration or other information, you can narrow down the search. You can also filter by hometown and birthplace. But I’ll demonstrate in a moment why the latter doesn’t make sense. The two came from Kötzting in the Bavarian Forest, but Kötzting does not yield any hits. Neither does Koetzting. Nor Kotzting. So I have to look through the list manually and finally find the two. They didn’t give the nearest town, as I would do when arriving in New York, but the name of their village: Traidersdorf.

There they are: Josef Vogl, emigrated in 1922, and his younger brother Franz Vogl, who followed him in 1923. (The last column contains the name of the ship on which they traveled.)

You can track this search or research your own relatives, because the database is accessible online. Free of charge. (You just have to register to use all the features.)

Let’s first look at Josef Vogl, because it was him who exactly 100 years ago gave us the reason to celebrate this centenary.

Right away I find out that he was born in 1893, that he arrived in New York on the ship “President Taft” on 30 June 1922 at the age of 29, and that he had set sail from Bremen. (After crossing the Atlantic twice, the “President Taft” was renamed the “President Harding,” so don’t let the image captions confuse you.)

This was already a proper cruise liner, not one of those creaky windjammers, half of which drowned. 18 knots. Space for 644 passengers, half in first class, half in third. The ship was only commissioned in 1922, so the paint still smelled fresh, the brass railings shone, and because it was summer, no one was afraid to hit icebergs, polar bears or penguins.

I could write about the highly competitive market for emigration to America now, about the cartels of the shipping companies, the emigration agents going around the countryside, with their brochures about the happy and prosperous life overseas, where everyone can have their own gold rush – or at least their own farm.

I could write about what the journey to Bremen meant for someone who, until then, only knew whatever villages could be reached within a day’s walk from the family farm. (This was before the time when the Wehrmacht sent German men on long trips abroad.) It’s actually not that far. One or two days by train, at a total cost of only 9 euros. But as far as I know, besides the two emigrating brothers, I am the only one in the extended family who has ever made it to Bremen.

I could write about the conditions on board, the differences between first and third class, the calm seas in summer, the stormy seas in winter, and the joy of a few weeks without any internet and television.

I could tell you that Josef Vogel was by far not the only one from that village who emigrated. They were a whole group of young men and women who left home together.

But I don’t want to write a whole book about this, and will thus attempt to reign in my wandering thoughts, leading them straight to the other side of the Atlantic, to New York. It was there where, on said 30 June 1922, some clerk made a meticulous list of all arriving passengers, with Josef Vogl being first in line. Whether this means that he confidently strode off the steamship as the first passenger, or if he was the sea-sickest of them all, or whether it was mere coincidence, I don’t know.

What I do learn is that he was 5 feet 6 inches tall (1.67 meters), had blonde hair, grey eyes and 50 dollars in his pocket. That would be about 800 dollars today, not really an impressive amount for starting a new life. I guess he had to look for work pretty soon.

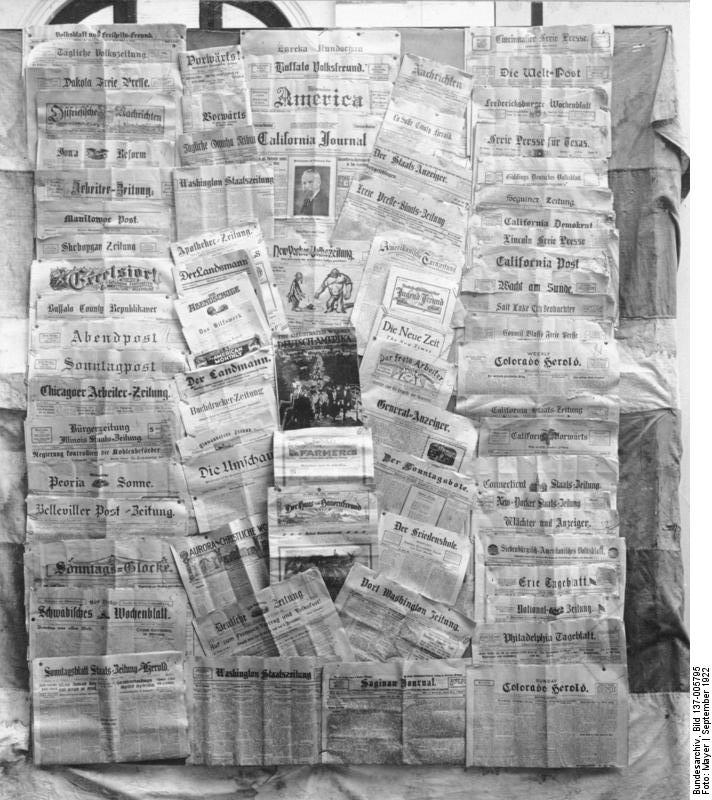

A very interesting column is the first stop where the immigrant wants to go until he can stand on his own two feet. “Friend Josef Sturm – Carroll JA” it says. For one thing, the name suggests that this is a friend from Germany. That wouldn’t be a surprise, since German immigrants liked to keep to themselves. They had German schools, German churches, German clubs and hundreds of German-language newspapers. There were German neighborhoods in the cities and German towns in the countryside, from Bismarck to Germantown.

I didn’t know what “Carroll JA” was supposed to mean, until I figured out that the J is meant to be an I: Carroll, Iowa. From Traidersdorf to Carroll, that’s like jumping from the frying pan into the fire. Or, as we say in German: escaping the rain into the water tower, which coincidentally is the proud landmark of this small town in the flat countryside. Well, if it wasn’t so flat, you wouldn’t need a water tower to get the necessary pressure to the water pipes. By the way, even when I was a child (1970s and 1980s), the ice-cold water on the farm in the Bavarian Forest came from the well in front of the house.

To this small town, which probably is quite a nice place, I now would have to travel to dig through archives, old newspapers and look for gravestones in the cemetery, if I wanted to pick up the trail of my great-granduncle Josef Vogl.

Would have. If we weren’t dealing with a classic case of chain migration. Because Josef soon got his younger brother Franz to join him. Franz arrived in New York, as I also learn from the online archive of Ellis Island, on 6 July 1923 at the age of 26. He too had sailed from Bremen, on exactly the same ship as his older brother, which by now was called “President Harding.” (That July 6th is my birthday and that I am happy about any support for this blog is only worth mentioning in passing.)

Everything was neatly noted down for him, too (line 9). It is apparent that it was the time of the economic crisis and inflation in Germany, because he only had 20 dollars with him. But he stated that his brother had paid the passage for him. Which was nice. I would do the same for my brother and sister any time if they can no longer stand it at home.

But the most helpful piece of information in this document is the address provided by Franz Vogl as the destination of his journey in 1923: “Brother Josef Vogl, 2301 17th Avenue, Altoona PA.”

That’s a real bingo! Even before I have to dig through old boxes in the archives of Carroll, Iowa, I already know that Josef had moved to Altoona, Pennsylvania, within a year and his younger brother Franz followed him there. Altoona, by the way, is also one of those German towns; it’s the Americanized spelling of Altona near Hamburg. They even got mountains there, the Allegheny Mountains.

And they got plenty of railroads and locomotive factories. When I reported this to my father, he remembered that Franz/Frank had told him during his visit to Germany that he worked for the railroad. So you see: It does make sense to share even preliminary results, because then somebody will remember something they didn’t know they knew. These “Unknown Knowns” were even overlooked by Donald Rumsfeld.

But the biggest step forward is that we have not only the city, but the exact address. You can’t get more bingo than that! And because Americans had rebelled against the General Data Protection Regulation in 1775, every street in the USA is now photographed, filmed, bugged by the NSA and posted on the interweb. Here is a recent photo:

The communist star above the porch does indeed suggest a family connection. On the other hand, the house doesn’t look like it was built in the 1920s. Maybe the neighborhood looked completely different back then? Maybe 17th Avenue was in a different part of town 100 years ago? Maybe someone got the address wrong?

To find out more, I will simply write a letter to this address. Or travel to Altoona to investigate myself. Or hope that someone from Altoona will read this article.

Of course, I could also search the databases. But I prefer to do it the old-fashioned way. And besides, I want to leave something for future articles on the search for the long-lost relatives.

And you can launch your own investigation, too! Because, as you have seen: Even if you think your family is boring and has always lived in the same place ever since the Mongols settled, almost every family has someone with a migration story.

But don’t trust artificial intelligence too much! You gotta work with a detective’s creativity, thinking in all directions. An example: Only when I looked at the document dated 30 June 1922 for the third or fourth time did I notice that the column “previous stay in the USA” indicated the period 1914-1921.

What? Did Josef already emigrate for the first time in 1914, when he was just 21 years old? I searched and searched, but could find no entry in the Ellis Island database. Close to despair, I remembered how stupid computers are and how smart people are, searched only for the last name, and sure enough: This time, his name is spelled as Joseph, not Josef. And the place of birth has been wrongly transcribed as “Fraidersdorf”.

At that time, he sailed from Antwerp, on a Red Star Line ship, whose former port facilities now house a migration museum. As luck would have it, I have been there as well.

In 1914, Josef Vogl was already drawn to Carroll, going – with four other migrants – to the nephew of someone whose name I cannot decipher. But it means that he may have lived there much longer than I had previously thought. So I do have to go to the archives in Carroll, Iowa, after all.

What would be of particular interest to me: How did he spend the time of World War I? With the US entering the war in 1917, anti-German sentiment was spreading. As a young man, was he taken to one of the internment camps?

The fact that migrants returned to their homeland after a few years and emigrated again later was nothing special, by the way. Since steamships had replaced the unsafe sailing ships and the journey had become relatively plannable, safe and comfortable, immigrants returned to Europe again and again. In order to get married. To take up an inheritance. Or to open a business with the money they had saved. Josef only stayed in Germany for one year, from 1921 to 1922.

In 1924, one year after Franz Vogl’s migration, the USA drastically tightened immigration rules and set quotas for certain countries of origin. This put an end to mass immigration. Good thing Josef and Franz made it in time. At least they were spared the Nazis that way.

And now I am curious about your own investigations into family history!

Links:

- All articles of the series “One Hundred Years Ago …”.

- More history, especially about German migration to the USA.

- The migration museums in Bremerhaven, Antwerp and on Ellis Island.

- Did you know that as the descendant of German immigrants, you can qualify for German citizenship?

Another interesting post on a very interesting topic. Those who are rooted need escape. Those who escaped need roots. I love the German word, Sehnsucht. On one of my dad’s old records, there’s a song about ‘Heimweh nach die Ferne and Heimweh nach Zuhaus.’

As a German immigrant kid in Canada I was without family and it felt a tad lonely, but now I know that that’s not such a bad thing. I like the view on the fence, with a foot in both (several) worlds. (Ukrainian-born mother, north German-born dad, me a Canadian). And some, seem to be children who belong nowhere, and everywhere, rooted in themselves and I think that might be the best option. I volunteer with immigrants and love hearing their motivations and goals in coming to Canada. It’s a cruel world out there.

When I meet people who have been uprooted and were forced to flee, some of them even several times, I totally understand the wish to settle in one place.

For me, on the other hand, spoilt by a life without war, that would feel like limiting myself to a tiny bit of this fascinating planet.

I can trace back to a great great grandparent who was Cherokee, and I’ve been told that we’re related to Col. William B Travis who was at The Alamo. I’m pretty sure my family were UK mutts before they became American mutts🤷🏼♀️ That’s allowed my mother’s side.

My father left when I was 3 years old and I don’t know much about his family except a very common last name🤷🏼♀️

I love history and personal family stories are interesting. I hope you’re able to find more information and of course, share it with us!

Unfortunately, I can’t trace back my paternal ancestors very far, because just two or three generations ago, the birth certificates all say “father unknown”.

I think my maternal ancestors may have been a bit more organized, but I haven’t started any research into them yet.

But now, I am wondering if I will hear from anybody in Carroll, IA or Altoona, PA .

I “know” 2 bloggers in PA, I’m not sure how close either is to Altoona. If you don’t hear from anyone, I will try to assist your research through my Blogging Buddies. I’m invested in the story now😁

As everyone knows, long back it was decided that for the stability of the world all those who are easily bored and therefore need to travel must be put into one country whose borders would be locked up. After several world wars they were successful and Germany was founded. Unfortunately the border guards thought it was their job to keep people out! As a result Germans began to escape and go elsewhere in very large numbers. Perhaps the experiment has not succeeded.

:-))))

I like this explanation of events!

Hi Andreas, that’s a really interesting story, about your uncles immigration to the US. After reading how you put together all the missing links, I think you have a yet undiscovered talent as a privat eye.

Thank you!

And I have only just begun with the investigation…

“Based on my own experience, I would like to add an often overlooked reason: Boredom. Or, to put it more positively: Curiosity. A sense of adventure. Wanderlust.” Yeah I planned really well my move to Uganda in late 2019 but did not happen until early 2021 due to a super long lockdown in Uganda and I still managed to get back to the UK in time and avoided a £2000 unnecessary government approved Covid hotel.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading about your family history and I don’t know if it’s still ongoing but a few months ago me and my sister were discussing a new wave of Germans immigrating to Paraguay and we jokingly said yeah they are probably tired of covid rules.

I came to the UK in 2004 aged 17 with 100 euros on my card and 20 euros cash that’s even less impressive mind you my mother had everything organised and I was a secondary school drop out and didn’t get a job until 2 months later, trust me I searched hard with my basic English, build connections and studied English at home it took me about 2 years to feel fluent and the rest is history.

You are actually right!

Those Germans who moved to Paraguay were escaping Covid rules, vaccination mandates or sometimes the tax authorities.

Funnily enough, many of those people are so steeped in their anti-government conspiracy that they believe that Germany is the only country that is a “Corona dictatorship”, as they call it.

I knew a family of German hardcore Covid conspiracy nuts who wanted to move to Spain to escape mask mandates and such. They were in for a shock when they realized that the rules were much stricter in Spain. After two weeks, they came back. :D

And those people who move somewhere to the chaco in Paraguay and are happy that they don’t have to wear a mask, well, they could just as well have moved to a small mountain village in Germany, where nobody would have cared either.

So do you live in Uganda now? :O

I hope the comment gets through now.

Nah, still in deadhill that sh*thole in Surrey but it’s ok.

The Uganda thing was for uni works and I saw that Uganda had exactly what I was looking for so I went.

I also went to Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan and Rwanda.

WOW!

That sounds like YOU are the one here who should be writing the travel blog!