Wannsee

Once again, I am on the train from the capital of culture to the capital of politics, from Chemnitz to Berlin. As I make this journey rather frequently, and because the Deutschlandticket limits me to local and regional trains, I like to vary the route from time to time. Sometimes I change trains in Elsterwerda, sometimes in Jüterbog, and today in Dessau.

The train is pretty packed already, so I have to decide quickly whom to sit next to. I like to choose people reading books. Or old people, because they have interesting stories to tell.

There is a young couple, recognizably from Israel. They are speaking Hebrew, and the boy is wearing a kippah. I sit down next to them, if only to prevent an anti-Semite from joining them at the next stop and ruining their journey.

Because I am not only forward-thinking like this and ever considerate of the well-being of all fellow human beings, but also polite, I greet them in Hebrew. This allows the two travelers to realize that I understand their language and to adjust their conversation accordingly, so as not to divulge any private or state secrets.

But the youthful voyagers seem to be on their honeymoon, because they keep conversing lovingly and laughingly.

Or they realized that my Hebrew is not that good. I have forgotten most of what I learned, and now only understand the numbers, as well as the words for beer (בירה), pizza (פיצה) and kibbutz (קיבוץ). Just what you need for a trip around the Holy Land. And the word “אצטרובל” [itstrubál] for a pine cone. It’s funny how the brain works. Many of the things I want to learn and memorize don’t stick. But that one word, which I heard more than 25 years ago in Ben Shemen forest, has occupied a brain cell as doggedly as an Israeli settler in the West Bank.

Almost as sweet as the word “אצטרובל” are the names of the places we pass:

Jeber-Bergfrieden.

Bad Belzig.

Borkheide.

Beelitz-Heilstätten.

Ah, now I finally know where this famous “lost place” is.

Brandenburg is like Upper Egypt. Some interesting ruins, but the rest is sand, and a flood every few years. (Upper Egypt is the part of Egypt which is at the bottom of the map, by the way. Just like Upper Bavaria or Upper Volta.)

I am digressing a bit, because I want to delay the inevitable. In fact, I would even prefer to redirect the train, if I could. Because I know which place we will pass soon.

“Well,” I tell myself, “they’re young people. That doesn’t mean anything to them anymore.” Besides, they are very happy and joking with each other. Probably not a honeymoon, after all, but the beautiful time before that fatal mistake that many people make despite my constant warnings.

If anyone finds this too negative: I am on my way to the family court, because two parents have been arguing for months about the days they see their son. Actually, people willing to marry and, above all, to procreate should be obliged to watch how quickly love turns into hate, before they are allowed to say “I do”. That’s probably why proceedings at the family court are closed to the public, as are only espionage trials. The state, concerned about the population pyramid, does not want people to learn the truth.

Wilhelmshorst.

Potsdam-Rehbrücke.

Potsdam-Babelsberg.

“Our next stop is Berlin-Wannsee. Exit to the right of the train.”

The girl next to me winces: “? ואנזה בגרמניה” (Wannsee is in Germany?)

I realize that Wannsee is just one of many Holocaust sites that she heard about at school. And because some of the most well-known of these – Auschwitz, Sobibor, Treblinka, Babi Yar, Majdanek – are located far to the east, the impression sometimes arises that the murder happened far away from the land of the murderers.

Perhaps that is why Germans appreciate these memorials in Eastern Europe so much. You can make a duty-bound trip there once, and then tell yourself that back home in Münster or Bremen or Fulda no one could have suspected, let alone known, anything about the Holocaust.

That is why I do not think much of carting all German school classes to Auschwitz, as is regularly suggested by politicians and by coach companies. They should go to Sachsenhausen if they are from Berlin. To Dachau if they are from Munich. To Neuengamme if they are from Hamburg. To Grafeneck if they are from the Swabian Alb. To Flossenbürg if they are from the Upper Palatinate. With thousands of concentration camps, Gestapo prisons, forced labor camps, euthanasia and other killing sites, you really don’t have to look far in Germany to see how ubiquitous genocide and other crimes were.

At the train station in Wannsee, they didn’t even bother to change the old signs. It still gives me the creeps each time I pass by.

Links:

- You can also get to Wannsee by taking the highly recommended Spandau hiking trail (part 1, part 2).

- But Müggelsee is a much more beautiful, peaceful and humane lake.

- More railway stories.

- Yet more stories from Berlin.

- And for those who are into more serious stuff, there is more about history and about the Holocaust.

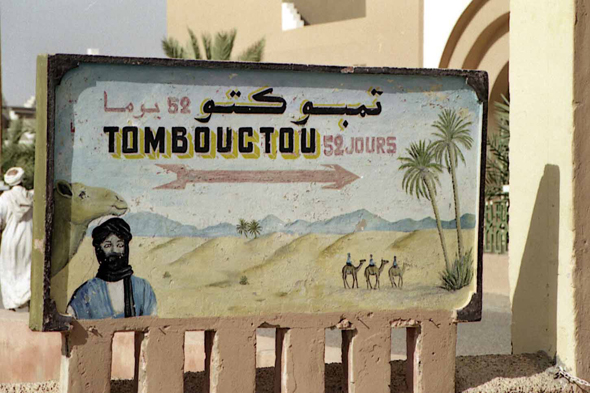

Yay, I am in Timbuktu!

Do you know that feeling?

There are places, cities and countries you have always wanted to visit, although you hardly know anything about them. The desire can be traced back to infancy, probably to some comic books you read as a child. An idea took root, sometimes fading in the background, but never disappearing completely. An inexplicable but deep longing.

In my case, Timbuktu is one of these dream destinations, although, for the longest time, I didn’t even know that it is in Mali. We Europeans, and it is important to be self-critical about this, all too often think of the entire African continent as a single large, exotic country.

The only cure against such ignorance is traveling.

And now, I am finally in Timbuktu!

Well, admittedly, not quite yet.

The photo was actually taken in the ODF Park in Chemnitz. The marble slab sunk into the ground refers to the twinning between the most beautiful city in Saxony and the pearl of the Sahara.

Originally, the municipal partnership was concluded in 1969 between Timbuktu and Karl-Marx-Stadt. But I guess you don’t terminate your friendships either whenever somebody changes their name. (Except, of course, when someone gets a doctorate degree and insists on being addressed as Dr So-and-so. This reminds me of a story I once heard in Eastern Europe: An academic from Germany, probably a scholar of literature or theater, went to Russia for a year. When she moved into her apartment, she insisted that her name on the doorbell include the “Dr”. As a result, she was regularly woken up in the middle of the night by neighbors asking for medical help or for antibiotics.)

I, for one, am thrilled that Chemnitz has such a fabulous twin city. Because that really is a reason to finally hitchhike to Timbuktu. The fact that you have to cross the desert for 52 days to get there is a bit daunting, but I guess that just means that I have to pack a few more cans of Coca-Cola.

In my opinion, it should be a general rule that one visits all the twin cities of one’s (adopted) hometown.

In Chemnitz, however, this is quite a challenge. Not only because the list is endless and some places are 8,000 km away. Inconveniently, Stalingrad is in a country where you can easily be locked away for a few funny remarks on a blog. And Düsseldorf, well, I don’t see why anybody would want to go there voluntarily either.

How about you? What twin towns or regions does your hometown have? Did you ever visit any of them?

The otherwise unassuming village in Bavaria where I grew up has an active partnership with the region of Modi’in in Israel, at the heart of which is an annual youth exchange. I went many times, first as a participant, later as a guide. It was a fantastic experience, from which I still benefit decades later, culturally and intellectually, personally and linguistically. So, if you have any children, send them forth into the big wide world! (And you better pay for the exchange or the Interrail ticket, or elsewhere your kids will have to abscond as stowaways.)

Password Swordfish

If you have ever been on the internet, you probably have plenty of passwords. Sometimes, the web pages prompt us to change them, and then, if we don’t use them on a daily basis, we forget about them and are locked out of our accounts.

The Marx Brothers already foresaw that problem in their 1932 movie “Horse Feathers”.

Karl Marx wishes you a wonderful autumn

This and the following photos are from the Park for the Victims of Fascism in Chemnitz, Germany.

It’s a large park, which is not a surprise, given the number of victims of fascism. And I am not even counting the guy who last year had his fingers cut off by a fascist, because he was a neo-Nazi himself. The two had conspired to fake the attack and blame it on the Antifa. I guess those guys should have their own park, dedicated to the victims of stupidity.

In any case, it’s a beautiful park, especially now in autumn. The public library is not far, and I often come here after having stocked up on books again.

And, as you may have guessed from one or two of the photos, the school buildings on the edge of the park are also impressive. Or, to be more precise, expressive. Because the Industrial School (at its time the largest vocational school in Germany) and the Agricola High School were opened in the 1920s and are outstandingly preserved examples of Brick Expressionism.

Too bad that most of us go to school at an age when we haven’t yet learned to appreciate such architecture. Many things in life proceed in the completely wrong order.

Saaremaa – First Impression

I am still on the island of Saaremaa.

As usual, it will take me a few weeks or months to process all my impressions and experiences and – much to the dismay of some readers – all the half-knowledge I have acquired about the history of Estonia and this particular island, and to transform everything into a properly polished article.

But as a teaser, here are a few photos and my initial assessment: This island is pure paradise!

Seriously, I am often so amazed that I fall into the lush grass, exhausted from sheer happiness and bliss. Or maybe it’s because I’m not used to riding a bike anymore.

In any case, I spontaneously extended my vacation by a week.

If the people here weren’t so peaceful, which unfortunately means no need at all for lawyers, I would have settled right away. But as it is, I’m glad that Saaremaa is very large and my cycling muscles are very weak. That means that I will have to return many times to explore the island in full.

And you can look forward to the detailed article and to a postcard!

Next Trip: Saaremaa

I almost feel guilty announcing yet another little trip as part of my journey to the center of Europe.

After all, I still haven’t even published the articles about the last geographical centers I visited – in Cölbe, near Purnuškės, in Europe Park north of Vilnius and in Suchowola. And then, there is the special episode about the geographical centers of Chemnitz.

My little history series has also been on hiatus for several months. As you see, the situation on this blog is pretty much a disaster.

Unfortunately, since I’ve returned to work as a lawyer, I’ve had far less spare time than granted to us under any human rights treaty. Divorces, child abductions, drugs and the new citizenship law all keep me on my toes. And a large part of my creativity is poured into legal briefs, which are only appreciated by a very exclusive audience. If at all.

In short: I really need a vacation.

So I’ve picked out the one of the supposed centers of Europe that I imagine to be the most beautiful and dreamlike of them all: the island of Saaremaa off the coast of Estonia.

Many years ago, I visited the smaller neighboring island of Hiiumaa. One of my secret travel tips for anyone who wants to do something against overtourism.

Back then it was the end of October and the first snow had just fallen. That’s why I’m going in September this time, when it’s still perfect weather for swimming, as the following videos show:

Hm, maybe I should pack a sweater. Just in case.

Actually, come to think of it, I am more into hiking than swimming anyway.

What I’m most looking forward to is the peace and quiet. Saaremaa is twice the size of Los Angeles, but only 36,000 people live on the island. And half of them are probably on the mainland to study or work.

I’m also excited by the outlook of staying on an island so sparsely populated that there is most certainly no mobile network or internet. I’ve already packed a backpack full of books and I am longing to take an offline break from all the problems of this world. (Unless some stupid country will invade Saaremaa again.)

So there will be radio silence until the end of September.

But after that, I hope to return to a regular publication schedule. I’ve put a freeze on accepting new clients until the end of the year, so that I have more time to write – and to study. I figured that in the gray fall and cold winter, your desire for travel stories from all over the world will be stronger than now in summer. At least that’s how I feel about it myself.

Links:

- Explaining the project “journey to the center of Europe”.

- The tourism office of Saaremaa.

- Previous reports about Estonia.

How does Bolivia deal with illegal immigrants?

Hier könnt Ihr diesen Artikel auf Deutsch lesen.

When I arrived in Bolivia, the arrivals hall at the airport in Cochabamba was so full that the police simply called out loudly: “Who is a local?” Anyone who raised their hand and their passport could walk through passport control without being checked. It was a concession to the late hour and to stressed travelers who wanted nothing more than to drop into bed after having flown halfway around the world.

I should have joined that crowd, but at the time I wasn’t yet confident enough that I would pass for a Bolivian.

So I got a one-month tourist visa at the airport. Free of charge. This I could extend twice for another month by going to the immigration office. When I told my Bolivian friends where I was heading, they all advised to take a few books, a bottle of water and the day off, because I would need to wait for at least half a day. In reality, you go directly to the friendly guy at counter no. 6 and before you can even sit down and start to explain your wish to stay for another month, he has already taken your passport, stamped it with the extension and handed it back to you. “How much do I have to pay?” I asked. “Nothing. Enjoy your stay in Bolivia!”

Three months per calendar year are the maximum allowed on a tourist visa. When I wanted to stay in Bolivia longer, I was overwhelmed with offers of employment contracts, volunteering contracts and marriage proposals, all of which could have served as the basis for a residence permit. It was also most surprising how many people could claim that “the head of the immigration office is my friend” or how many people had “a sister-in-law at the very top of the immigration department”.

But I didn’t want to do anything shady. Also, I was already intrigued by the prospect of getting arrested to take a look at the famous Bolivian prison system. Once, after my visa had already expired, I was held up at a police checkpoint. I was already hoping to be taken away in a van with metal-grilled windows, on the way to explore the justice system of a Latin American country. The officer checked my passport carefully, looked at me, looked at the visa with sorrow, looked back at me and handed my passport back. All he said was: “I am glad you are enjoying Bolivia, Señor.”

So I stayed four more months, illegally. From now on, whenever you are ranting about “illegal immigrants”, please remember that it’s people like me that you are talking about.

Bolivia is not only friendly to visitors, but also quite smart. Instead of locking up immigrants, building walls or deporting people, all of which would cost a lot of money, they impose a fine.

So I worked hard for a few months until I had saved thousands of bolivianos. The day before my planned departure, I went to the immigration office in La Paz, pockets filled with stacks of money, to pay the fine.

I was very nervous. After all, I was in a foreign country, I had committed a crime, I was on my way to the authority responsible for prosecuting these crimes, and I had to explain everything in Spanish.

There was a soldier at the gate of the immigration office who told me that unfortunately they were closed to the public on Wednesday afternoons.

“Oh,” I exclaimed, ”that’s sad. Because I still have to pay a fine before I leave the country tomorrow.” For the hundredth time in my life, I made a resolution that I would never again wait with important things until the last day of the deadline.

No matter what Tucholsky said about soldiers, this one was nice. He recognized my self-inflicted plight and said: “Well, come on in and we’ll see if anyone is still here.”

In fact, there was a lone civil servant at one of the counters. He had probably had been looking forward to a visitor-free afternoon, finally allowing him to sort through files or read the ministry’s new circulars.

But he was very friendly and offered me a seat and a cup of tea. When I started to apologize profusely for having lived in his country beyond the permitted time, he reassured me: “Señor, you don’t have to apologize for that. It can happen to anyone.” Whenever he noticed that I was nervous, he would say: “Don’t worry about it”, as if I had forgotten to get off my bicycle at a zebra crossing.

Zebra crossings were invented in Bolivia, by the way, but that’s another story.

When the official took my passport and saw that I had been in the country illegally for a whole four months, he too became concerned. Normally, tourists overstay by a few days because they miss their flight or get lost in the jungle.

He then set about calculating the fine that was due. Until then, I had read different figures, from 20 to 26 bolivianos per day.

The officer took the time to explain in detail how the fine was calculated, and for the benefit of other travelers, I can reveal that the amount is 12 UFV per day. An UFV is an unidad de fomento de la vivienda, which is an accounting unit introduced to make payable amounts independent of inflation. It is calculated by dividing the Consumer Price Index of the present month by the Consumer Price Index of the same month of last year, taking the 12th root of that result, then calculating the nth root, whereby n is the number of days of the present month, and finally multiplying this result by the value of the UFV of the previous day.

I did not understand it.

The officer had a computer and a calculator, but he preferred using a pencil and lots of paper to do his calculations. After about 10 minutes, he pronounced that I would have to pay a little more than 3,000 bolivianos.

“Good,” I said, because that was exactly the amount I had saved up. Just one boliviano more, and I would have had to sell another kidney.

“Not good at all,” said the official, who was visibly shocked by the hefty amount.

“That doesn’t matter. I knew it beforehand and saved accordingly.” Somehow, the roles had been reversed, and it was me who had to tell him that he needn’t worry.

“But the other tourists only ever pay a very small fine.” He used the word multita, the diminutive of multa. It’s difficult to translate, partly because you can’t imagine an ICE agent talking about a teeny-tiny fine. “It would be unfair if you had to pay so much more.”

I couldn’t think of any more arguments, other than pointing out that I even had the money with me and could pay the full amount on the spot.

“No, no,” he said in horror, ”let’s first see if there isn’t some kind of exception in the law. An upper limit perhaps, so that you only have to pay for one or two months.”

He called his boss.

The head of the immigration department came down immediately, greeted me warmly, also told me not to worry, and then discussed the case with his officer. I stood there, a lawbreaker, while the two law enforcement officers discussed whether there were any exceptions in the law that could be used in my favor. From the expressions on their faces, I realized that there was no easy solution.

Finally, the boss asked me how I was going to leave the country. By plane or by bus?

“I will take the bus to Peru,” I said.

“Very good!” he exclaimed with relief. “Then you won’t pay anything now, and if you get checked at the border, you can still pay there.” He only half-heartedly concealed his hope that I would somehow slip through, smiling about the solution he had found.

I don’t know why people have such a bad opinion about government offices. People are really helpful there. (A completely different mishap happened on the way to the border. That was a bit much for one day, even for me. But it wasn’t the authorities’ fault.)

Unfortunately, I’m the type of person who can’t just put my passport on the counter without saying a word when leaving the country in the hope that nobody will notice. When I entered the Bolivian border post in Kasani on the sores of Lake Titicaca, I admitted it straight away: “I think I have to pay a fine before I’m allowed to leave the country.”

Because all the other passengers on the bus were less criminal than me and therefore quickly processed, all four counter officials soon gathered around me to hear my story. “If you like Bolivia so much, why didn’t you simply get married to a Bolivian woman?” one suggested. As they questioned me with serious curiosity about my travels, one of them did the same and equally complicated calculation of UFVs and bolivianos.

Again, the state representatives were shocked by the amount owed, discussed it among themselves and recalculated it several times. The border officials had smartphones with calculators and internet, which they used to exchange WhatsApp messages with their wives all the time, but for the complicated calculation of the 12th root of something, they too preferred paper and pencil.

Here too, they discussed whether there were any exceptions and whether something could be tweaked until one of them had the idea: “Let’s call the head office in La Paz, maybe they can think of something.” That was the office where I had been the day before.

I don’t know if one of the two men from yesterday was on the phone who would still remember me. In any case, the order came from the ministry to show no mercy to any gringos.

The border officials told me that with my fine of 3,082 Bolivianos, I would unfortunately only receive the silver medal. They had already taken more than 4,000 bolivianos from another traveler. I was disappointed.

By the way, all of this is done strictly above board. The payment is not a bribe. You get a receipt, lots of handshakes and best wishes for the trip. You are also given the useful hint that you are no longer allowed to enter Bolivia in the same year, but as the border official said with a broad smile: “From January 1st next year, everything will be forgotten and you will be very welcome again!”

As you can see from the receipt, I committed the “grave violation” of “staying in Bolivian territory in an irregular way”. The fine was 25.68 bolivianos per day. That’s 3.34 euros (3.70 US dollars) or exactly 100 euros per month. Not much for getting to live in the friendliest and cutest country in the world.

The following January, I immediately moved back from Peru to Bolivia. I only overstayed my second stay by a week or so, but this time, I wasn’t the least bit nervous about the small fine.

Links:

- More articles about Bolivia.

- Ironically, I now work as an immigration lawyer.

A Masterclass in Storytelling

For the mass graves, turn right in 300 meters

Just a regular marker in Central and Eastern Europe:

I stumbled across this one as I was walking to Europos Parkas from Vilnius, while looking for the geographical center of Europe. But more about that in a separate report, hopefully coming soon.

Whenever someone brings up the argument of Europeans allegedly having a superior culture or history, I have to think about the whole continent being dotted with mass graves from the Baltics to the Balkans.